by Cynthia A. Kase

by Cynthia A. Kase

Read on FEI Daily

Without investment risk none of us would make any money in the markets, but managing trading risk as a financial executive is a lot more complicated than one might like.

Often risk limits are set arbitrarily and impacted by trader performance, units traded, the typical risk per trade, and whether the risk per trade is statistically appropriate. If the risk is too low, that means you constantly see your stops hit and exceed your limits, only for the market to turn back in your favor. If the risk is too high, you will stay in losing positions too long, and give up too much on profitable exits.

Proper stops cannot be placed purely on one’s comfort level, or budget, but are dictated by market conditions and volatility.

STEP 1: Understanding Trader Performance Risk and Percent Chance of Loss

Everything else being equal, a trader with a good track record has a lower probability of losing the risk limit than a trader with a poor one.

Corporate traders are often inexperienced, as I was when I was transferred into international energy trading from engineering in 1983 (just as the crude oil contract was introduced). So it’s not always a valid assumption professional traders are competent or well-trained. Back then, energy traders only used fundamentals (defined as research combined with speculation), and setting risk limits as a gross value made sense. The best computing power we had on the trading floor was an Intel 8086 beige-box desktop, and streaming data evaluation — available on today’s Bloomberg terminals — was not within reach.

Many years later, computing power can push lots of streaming data through very sophisticated algorithms evaluating risk in portfolios, even if they contain thousands of securities, in the blink of an eye. Thus we can set risk limits and control risk in a much more granular and nuanced way. It’s not a question of either fundamentals or technicals. Today, there’s no excuse not to do both.

This first step involves understanding the math that underlies basic risk calculations, and how they are impacted by trader performance. Here are the key formulae, derived from game theory.

A = RL / {In(P) / [ln(1 – W) – ln(W * R)]}

RL = A * {ln(P) / [ln(1 – W) – ln(W * R)]}

P = EXP ({RL * [ln(1 – W) – ln(W * R)]}/A)

Where:

A = Amount of Risk per Trade

RL = Risk Limit, or Total Capital

Willing to Lose

P = Percent Chance of Losing RL

W = Percentage of Time “Win”

R = Win-to-Loss RatioLet’s assume the risk limit is $100,000. The trader will be “shut down” if that much is lost. However, there’s a big difference between a 25 percent chance of losing $100,000, versus a more tolerable 0.25 percent.

The question becomes how much of a chance is being taken of losing “everything”. W is the percent of times a profit is made. So if 100 trades are taken and 55 are winners, the W value is 55 percent, or 0.55. R is the ratio of the average wins, say $10,000, and the average losses, say $5,000, with R, then the win to loss ratio equal to 2.0.

Using various inputs with a range of P values produces the following:

The table shows risk-of-ruin can be by cut by a factor of 10 but cutting the risk per trade by half. Dropping from 1 percent risk to only 0.25 percent, a 75 percent further reduction, only takes a 24 percent cut. So, cutting the amount risked per trade has outsized payouts relative to the probability that the RL will be lost. Also cutting risk per trade by about one-third would allow a more conservative assumption of W = 1.5:1 for untried traders.

With a percentage of winning trades of 40 percent, the win-to-loss ratio would have to rise to 3.67 for the same results. Many pundits point out that it’s possible to have a winning track record with less than 50 percent wins. The problem is that this scenario usually relies on outlier wins, as opposed to steady wins in the 3.5 to 4.0 range. Since outliers are, by definition, not typical, one must be wary of such assumptions.

Kase has developed more complex Monte Carlo models to simulate outliers in wins and losses, and the percent of wins for a more nuanced view, and to track trader performance against statistical expectations. However, plugging the formulae above into a spreadsheet is a good place to start.

Step 2: Measuring Risk

Step Two involves translating risk per trade into risk per unit and units per trade in a non-arbitrary fashion.

The risk per unit is the point at which a stop would be placed. It’s necessary to assess the degree of risk inherent in a given market, and design a stop suitable for it. Being ex-Navy, I like to use a nautical analogy. Sailors must evaluate conditions, such as the height of the waves, wind speed, direction, and the like. You risk ruin choosing to sail a dinghy in a raging Atlantic storm, because its price is consistent with your budget.

The primary measure of trading risk is True Range (usually written TrueRange), and it is this value that should be the basis of setting stops. TrueRange is proportional to local volatility. TrueRange = maximum(H, C[1]) – minimum(L, C[1]). This is similar to a bar’s high low range, but includes gaps between the previous bar’s close and the current bar’s high or low. Chart 1 below shows a TrueRange (red) and High-Low range (blue) as identical. The middle chart shows the low of the TrueRange at the previous day’s close, below the low, and to the right also at the previous day’s close, above the high.

Nomenclature is H = high, L = low, C = close, and [n] = bars back. This bar is always bar[0], though it’s customary to drop [0], as it’s understood.

TrueRange may be calculated over multiple bar lengths, such as sets of three bars.

STEP 3: The Amount of Risk per Unit, or Setting Stops

Simple stops might be based on a multiple of Average True Range (ATR). Typically a value of around 1.7 would be considered a warning, or even an exit if broken on a closing basis, and a multiple of 3 to 4 works for a must-exit point. Depending on your exit strategy a stop using a multiple between 1.7 and 4 should be used to determine the risk per unit.

ATR is available in most, if not all, charting platforms, but if yours doesn’t have it, it’s easy to calculate on a spreadsheet.

Because the standard deviation of True Range varies, Kase developed an improved stop called the DevStop. It uses multiple standard deviations over the mean TrueRange based on two-bar sets, corrected for right-hand skew. Using two-bar calculations helps capture some directional information on whether bars are overlapping due to oscillations or moving directionally. Because these stops are statistical, a setting of 1.0 standard deviations over-the-mean captures about 84 percent of the observation on a cumulative basis.

Chart 2 below shows the ATR stops in the top pane and DevStops in the lower, both based on 30 periods. The placement of the stops on the chart is driven by a 10- and 21-period simple moving average. When the 10-period moving average is below the 21-period moving average, the stops “trail” the lowest low, to which they are added, and vice versa.

STEP 4: As Time Frame Rises, Risk Rises on a Diminishing Rate.

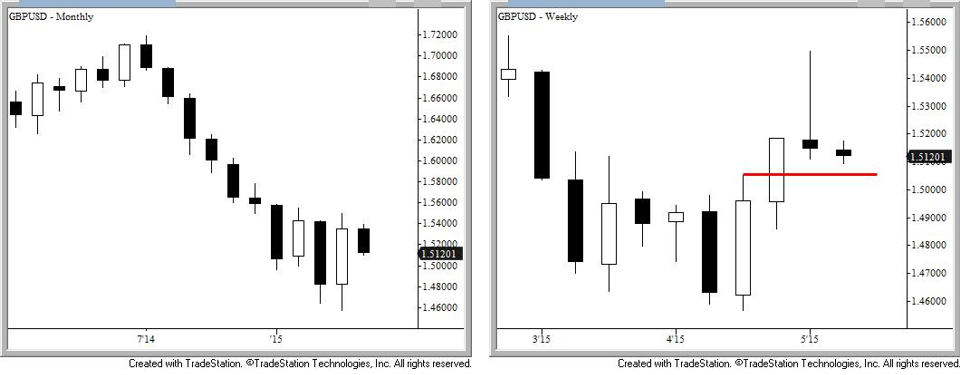

Even though you might be looking at a daily chart, weekly charts are often preferable, and sometimes even monthly, as the oscillations in many, if not most, securities are statistically too large to manage on a daily basis. Remember the market doesn’t care about your budget. If the market dictates a monthly chart, so it is. The key is to know how large your stop must be and set your other risk limits accordingly. Keep your risk profile at the same or a lower level by adjusting units traded.

By doing this, keeping risk the same, you might actually be improving performance because you will be hitting stops and churning much less often, and price action smoothes out.

A big benefit in moving up in time is that the risk only increases proportionally to the square root of time, and in real life, often less. So moving to a higher time frame has diminishing costs. Moving up by a factor of 25 only increases risk by 5, and from a daily to a monthly about 4 or so. Again, in actuality the impact of outliers is often felt less by the bigger bars, so the risk increase might be dampened.

The penalty is on the downside. If you want to cut the risk inherent on a daily chart by a factor of 3, you need to trade 9 bars per day. Dropping down to a lower time frame, where an oscillation on a daily bar becomes a trend on an intraday is an option, but with diminishing value. The impact of outliers and gaps hits harder. Also this requires active trading that is impractical for moderate to large volumes.

Case Study: AAPL

Let’s look at Chart 3 below, two AAPL (Apple Inc.) charts. The one on the left is a daily and on the right a weekly chart. Each shows price activity from about March 2014 to January 15, 2015. Each chart has double-sided DevStops, with a 10 and 21 simple moving average in the bottom pane. Here the “normal” stops, in the direction crossover, are shown in brown. If there’s a “mini trend” in the opposite direction, those are shown in aqua. The reason these mini-trend stops are shown is that sometimes traders reverse positions before the moving averages do, and therefore, traders have asked us for stops in that case.

Looking at the stops changing color and the moving averages crossing back and forth, it’s clear that although AAPL was trending, the daily was choppy. The weekly only had one back-and-forth cross early and then moved up cleanly.

One might argue that it’s only natural for a weekly to have fewer crossovers than a daily, but in this comparison, the daily is quite choppy for a trending market, regardless. (I call this type of market “hybrid” as it is choppy and trending at the same time). Note the moving averages are used to illustrate the point that regardless as one’s choice of system, there would be a fairly high churn on the daily, anyway. I count about 16 moving average crossovers, 12 hits on the first level stop, six of which followed through to hit the second level. Only the early December hit was significant.

On the weekly, price action looks fairly clean, and the first level stop was hit only twice: once during a corrective period in the fall, and then on the week ending December 12, 2014, at which time there was a close below it. Thus the weekly would have allowed the trade to run at least until then. This is not to suggest that the daily be ignored altogether, just that it should not be the primary chart monitored.

Take a closer look at the smallest of the purple values on the right of each chart. The daily’s value is 6.56 and the weekly’s is 10.44. This is the first stop’s risk. If we assume that one would exit on a close below this stop, the daily has eight exits, while the weekly only one, on December 12. However, the risk on the weekly is only 1.6 that of the daily even though the time has increased by a factor of 5, with a predicted increase of 2.23 (√5) or less. As noted above the actual increase is usually less.

The fact that risk of about $10.44 per unit must be taken might be unpleasant. However, if you look at the red arrows, it’s obvious that the statistically based stops inherently match up with highs and lows on the weekly, not the daily. Finally, look at the small number in green between the risk values. This is a gauge of chaotic activity, based on a ratio of standard deviation versus average range measures, called the Kaos ratio. The reading on the daily is 0.39 versus the weekly 0.33, showing that with the lower value, the weekly is probably a better choice.

STEP 5: Crunch the Numbers

You can determine the risk per unit using the simple stop calculation, and put it into the formulae in Step One to figure out how many contracts to trade. The stop also can determine loss triggers at which you will monitor trades and traders more closely.

To cut out the spreadsheets, I’ve designed an algorithm that automatically pulls the largest stop value and does all the calculations. Based on a risk limit of $100,000, win-to-loss of 1.5, wins of 55 percent, and 0.25 percent, 0.50 percent, 1.0 percent, and 2.5 percent risk of ruin (as inputs into the algorithm), the risk per trade and units per trade are returned in the Chart 4.

Comparing (on either chart) the “red” at a 2.5 percent risk of ruin with the “blue” at 0.25, a 10 fold reduction, a decrease of 38 percent, or a factor of 2.6 is required. So modest reductions in trading volume disproportionately diminish risk.

The risk per trade is the same on both charts, as it is driven purely by the manual inputs into the model. The units per trade is the risk per trade divided by the risk per unit (the stop value) pulled from the chart by the algorithm. Here there has been a five-fold increase in the bar length, but the units per trade drop by less than 30 percent.

Simple risk of ruin calculations can be used to determine risk limit parameters. The key is to use TrueRange based stops to gauge the risk per unit. Risk does not increase at the same pace as bar length increases, which is favorable to using longer bar lengths. Reductions in trading volume disproportionately decrease risk. If stops are hit often, try higher bar lengths. With the five steps done correctly, you can use stops to monitor individual trades and traders, as well as performance over time.

Cynthia A. Kase, CMT, MFTA, chemical engineer, oil trader, risk manager, and highly acclaimed market technician, is president of Kase and Company, Inc., CTA which has two foci: advising corporate and institutional energy clients on trading, hedging and risk management issues, and another as a cutting edge software developer of technical forecasting and trading studies, and algorithmic solutions to trading issues.

by

by